Even though this is being assigned early, treat it like a normal final exam: sit down and give yourself 1-2 hours to complete it. Of course, you can do it early or work on it on and off during the week. However, the exam is due by on Tuesday. Just don't look at this as a paper per se; it's not a paper, just a long-answer question on a typical exam.

Choose ONE of the following scenarios to write a developed response, approximately 3-4 pages double spaced…

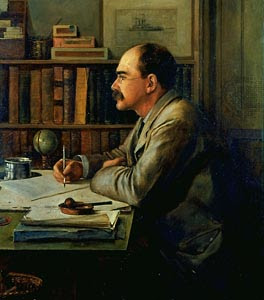

1. You are a high school teacher, and want to teach Kim to your advanced English Literature class. Unfortunately, the administration, which only knows Kipling from the poem “The White Man’s Burden” (www.fordham.edu/halsall/mod/Kipling.html), claims he is a politically incorrect, racist writer who has no place in a modern classroom. Defend Kim as a colonial text that is critical of colonialism and plays into many important postcolonial ideas and writing. Use the book for support and be as persuasive as possible—and don’t give in, even if it does cost you your job!

2. You are the director of the Indian Ministry of Tourism, and V.S. Naipaul’s book, An Area of Darkness, has just been released to tremendous acclaim. A great danger of this book is that it can hurt tourism and make the country synonymous with caste injustice and excrement. Write a response to specific passages of Naipaul’s book challenging his biases and national identity. For example, many have accused Naipaul of being too “English” and seeing India India

REMEMBER, make a persuasive argument for Kipling or against Naipaul, and support this with a close reading of the text. Don’t generalize or gloss over tricky issues; try to confront them head-on using Kipling or Naipaul’s actual language. Also consider who you are as you write this: an educator who believes in the power of Kipling’s thought…or a government official who is outraged when an “outsider” tells the world the “truth” about India

Good luck!