|

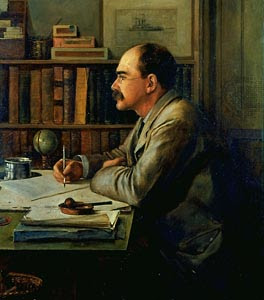

| Artwork by Kipling's father based on Kim |

Kim is Kipling's best known novel and the only one to gain complete critical admiration (his first novel, The Light That Failed, is largely considered a failure, and his other big one, Captains Courageous, is considered children's lit and rarely discussed). The novel follows the education of Kim, a half Indian, half Irish orphan who attaches himself to a Buddhist lama who adopts Kim as his "chela" (pupil, but in a religious sense). Kim eventually ends up in English hands and becomes an agent in "The Great Game," which was the struggle between England and Russia for control of Asia (Russia threatened to invade India for some time, and like England, was mired in endless skirmishes in the mountains of Afghanistan--sound familiar?). One general thing the novel asks is what path will Kim (as a representative of India, half "English," half "Indian) ultimately take: will he choose the East or the West? England or India? Tradition or Empire?

Other ideas to consider...

* How is the lama portrayed in the early parts of the novel? He is seen by some critics as wise, representing Kipling's deep love for Indian/Eastern spirituality; to others he's a clown, a buffoon, and mere comic relief.

* Why is Kim drawn to the lama? What does he see in him?

* How does Kipling contrast the lama with Mahbub Ali? Why do they both appreciate Kim--but for different reasons?

* Examine the narrator's tone/perspective in these opening chapters; do we hear an imperialist giving a condescending 'tour' of India, or is it more in the style of Kipling's travel writings such as "Edge of the East?" Consider this passage from Chapter II: "All India is full of holy man stammering gospels in strange tongues; shaken and consumed in the fires of their own zeal; dreamers, babblers, and visionaries: as it has been from the beginning and will continue to the end" (Longman, 27). Note that Chapter II opens with a quotation from the poem featured in "Edge of the East."

* How does Kim respond to the Indian landscape/people? Is he aloof from it like an Englishman, or does it, as Kipling writes in "Home," "[speak] with a strong voice, recalling many things; but the most curious revelation to one man was the sudden knowledge that under these skies lay home and the dearest place in all the world" (Longman, 256)?

* What do you make of the poems heading each chapter, all of which are drawn from Kipling's own verse? How do they comment on the themes/actions of the chapter?

* Why does the lama give up Kim to the English? Is this part of the 'comedy' of his character, or there something else at work here?